The checkpoint game

“Feee -ky!”

Reem came sweeping into the office with an agitated clatter of bracelets. She always moves like a whirlwind, but I can tell when something has happened to disturb her: ‘v’ becomes a ‘f’ and she stretches the first syllable of my name to breaking-point.

“Do you know what has happened to me in this sheckpoint today?” she demanded, jabbing her thumb at our rear wall. (‘Ch’ becomes ‘sh’ as well.) “I could not believe my eyes, my ears, my own ears I could not believe! Do you know what they are doing now?”

I glanced nervously at the brimming coffee cups on the desk. She was gesticulating with enthusiasm and I could see a third-degree burns incident occurring if we weren’t careful. I managed to shepherd her into her chair (an impassioned Reem is a bit safer when she’s sitting down) and discreetly transferred the cups to a side table. Then I settled down and prepared to hear yet another checkpoint story. Every Palestinian has their checkpoint stories. Listening to these weary catalogues of mundane humiliation and everyday hurt, I always wish I could change the endings, but I can’t. The only thing left for me to do is listen.

The checkpoint overshadows life in Bethlehem. Known as Machsom 300, it bisects what was once the main Hebron-Jerusalem road. As you approach, you are likely to be mobbed by eager taxi drivers offering to take you to Hebron, Ramallah, Jericho – everywhere but Jerusalem, where they aren’t allowed to go. They don’t accost me any more, as they know I’m not a tourist, but in the past I could never manage to sneak into the machsom without being besieged. “Not today, thank you, I’m going to al-Quds,” I told one cheerful driver who had come leaping over to suggest a jaunt to the soap factory at Nablus. I always felt apologetic and even guilty when I said those words, because I knew that in all likelihood these men have family and friends in Jerusalem, and that they would practically give their right arms for the unfettered access conferred on me by my British passport. This particular driver wasn’t deterred. He beamed. “I will take you there! And after Jerusalem, Paris! Siberia! New York!” We all burst out laughing, but the apologetic guilt bit in deeper.

Jerusalem is five miles down the road, and there are two ways in. One is marked ‘Humanitarian Lane Only/Tourists’ Lane’. Carrying my burgundy passport, I can walk right up to the door in the separation wall, pass through a turnstile, and enter the main checkpoint, along with other aid workers and tourists and a few hand-picked Palestinians who are judged to be old enough or sick enough to merit the privilege. Everybody else must use the passageway simply marked ‘Entrance’. Unlike the tourism lane, this lane is enclosed with bars, to ensure that the queue remains as orderly as it can be when there are hundreds of people packed in here together.

As a Palestinian Christian, Reem had applied for a forty-day permit to cover the Christmas period. Almost the entire neighbourhood had applied, and the wait to find out who had been issued the coveted slip of paper was tense: the decision-making is a completely arbitrary process. It is common for the military authorities to grant permits to everyone in the family except for one or two people, a policy that seems to have no rationale except for a desire on the part of the IDF to be mean-spirited party poopers. The Christmas before last, everyone in my host family got permits to go to Jerusalem except the father. This Easter, everyone in a neighbouring household received a permit except for the eldest daughter, eighteen-year-old Rouba. Rouba is a leader in the Girl Guides, and she was supposed to be taking part in the Palm Sunday parade with her Guide company. Now Rouba is a very determined sort of person who has taken to heart the Girl Guide motto, ‘Be prepared’. Few situations faze her. She sneaked into Jerusalem illegally in order to join the festivities. I was terrified that she would be caught and sent to spend her Easter in jail, and that night I couldn’t rest until her reassuring knock at my door sometime after midnight let me know she was home safe.

Reem didn’t have to go through any of this at Christmastime. She was awarded her permit without having to appeal, bribe, or beg, and one balmy December day she set off for Jerusalem with her two young daughters, planning a day of shopping and fun. The trio passed through the barred-in passageway and reached the first of three inspection points. They crossed without incident. Next came the body scanners, and finally a second document check, complete with a biometric hand scan. A security official took Reem’s ID and permit and scrutinised them closely. Then he looked at her daughters, who are both in primary school. “Where are their permits?”

“Excuse me?” Reem asked in disbelief. Children under sixteen aren’t given permits. They are allowed to pass the checkpoint providing they are accompanied by a permit-carrying parent.

“Their permits.”

“But my eldest daughter is only eleven! She will not get a permit for another six years!”

The official shrugged. “No children are to pass without permits. Those are the orders.”

Now another family had appeared behind Reem, clutching their paperwork – a Muslim couple with three young children of their own. “Do you have permits for these children?” the official demanded. Bewildered, the mother gave the same answer as Reem, and was told with the same implacable indifference: “Then you are not going through.”

As Reem related this story, her voice still shaking slightly, something a local journalist and relative of my host family had warned us about last April flashed into my memory. Jenny had found a baby in our neighbourhood who had been issued with a Jerusalem permit. At the time I was sure that the permit must be a spoof, a satire, because who gives photographic identification to babies? One baby looks very much like the next to my untrained eye – squashy, red, crying, liable to bottom explosions, you know the sort of thing. But it turned out to be true.

in our neighbourhood who had been issued with a Jerusalem permit. At the time I was sure that the permit must be a spoof, a satire, because who gives photographic identification to babies? One baby looks very much like the next to my untrained eye – squashy, red, crying, liable to bottom explosions, you know the sort of thing. But it turned out to be true.

Another twisted piece in this jigsaw slotted into place at Christmas, a fortnight before Reem’s altercation at the machsom, when my colleague Toine’s children were issued with permits too. Toine was concerned enough to write this:

A bell rings in my head. About half a year ago it happened for the first time that at the Bethlehem-Jerusalem terminal soldiers asked our daughter Yara for a permit. At the time we thought the soldiers were simply in a crazy mood…But it seems there is a method behind the mad game. In the occupation machinery, it happens that slowly, covertly and with intervals, a new measure is introduced like in this case preventing access to Jerusalem for children. The measure is tested out here and there and now and then, thus making the public acquainted with it while creating confusion and ambiguity so as to soften people’s anger and will to resist it – up until the moment when the measure is publicly declared and fully implemented. In this way, piecemeal, the connection of West Bankers with Jerusalem is eroded, and Bethlehem and other areas are becoming more like a prison. Israel’s occupation is a process, sometimes overt, such as in the case of Wall building, but sometimes covert and gradual…Yara is almost excited having received this large permit with its official text and special lay-out. Some of her friends also got one – but not all. Imagine, the permit system now plays with the hearts of children as well. Yara asks me to leave a permit behind the flower plant in front of our house for one of her friends to take. Tamer (9) also gets a permit, but he protests: “Why do I need one?”

“The Muslim family were not going anywhere, they were trying to argue. The soldiers were being very rude with them. Then they looked at me again,” and Reem’s dark eyes flashed fire, “and suddenly one of them spoke to me in Hebrew. I do not understand Hebrew, but the Muslim lady, she did, and she translated. She told me, he is saying, are you Christian, if you are Christian I will let you and your children pass.”

Reem was out of her seat and pacing again. It was as if there were springs in her feet. “How dare they! You know why they do this? They do this to create ill-feeling between us! They like to divide us as Palestinians, they try to create the enemy feeling, the discord, it is part of how they control us! How can I walk through to Jerusalem with my daughters, and let those Muslim children stand there and see this bad thing? So now I am angry, and now I am screaming at the soldier. He said to me, ‘If you are Christian I give you special permission to pass.’ I shout at him, ‘You are right I am going to pass, but I am not going to pass because I am Christian, I am going to pass because it is my right, and this family will pass with me! They have got your permit, they have followed your rules, and now you are playing with them! I tell you, in one second I will take all these stupid permits and rip them up in front of your faces!”

Reem’s words were ricocheting round the office like bullets. She took in a big gulp of air, and continued. “The Muslim family were saying to me, ‘Sister, please pass, it is your Christmas feast and it is nice for you to see Jerusalem.’ I told them, ‘I can’t bear that they do this to us in front of our children.’ But they are saying to me, ‘Don’t worry, you know they will do the same thing to you on Eid.’ This is true, they are right. But still it hurts me. They divide us and they try to make us different from what we are. I will not be what they make me. I am Palestinian. I told this to the soldiers very loudly.”

“So I gather,” I said dryly. “I shouldn’t imagine that you would tell them anything quietly.”

Reem chuckled. “My daughters, they were panicking. They told me that I have to be good in the checkpoint so that the soldiers continue to give us a permit and they can go to the beach. Do you remember the time when Maryam said to me, ‘Mum, why don’t you give the Israelis our house and the car and see if we can get the beach instead’? I need them to understand that there are more important things than the beach. Eventually I agreed to pass this checkpoint, and on the other side there was a woman who had heard everything. She was an Israeli woman, and I asked her, ‘Are you a Woman in Black?’ and she said yes. She listened to my story.”

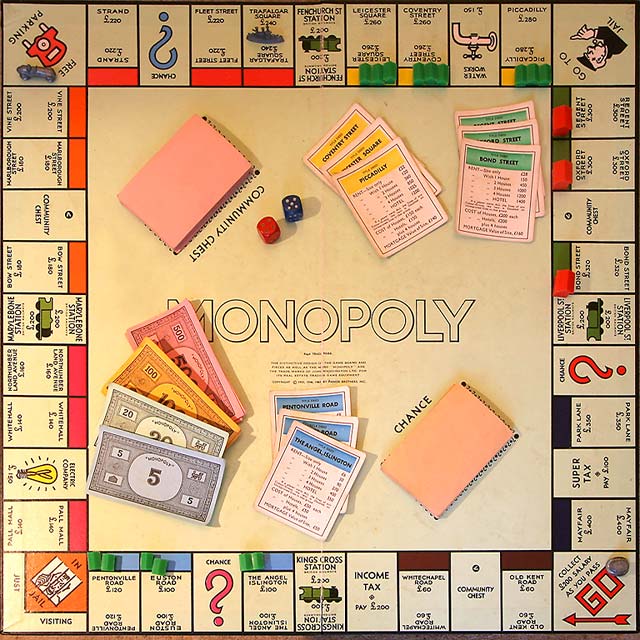

Women in Black and Machsom Watch are peace and justice groups composed of Israeli women. Among other things, they monitor the checkpoints and try to increase public understanding of how they affect Palestinian life. At our organisation we have developed a more light-hearted way of promoting awareness. We have produced a simple board game, ‘Checkpoint’, which is used to introduce visitors to daily life as experienced by Maryam, Rouba, and everybody else on this side of the wall. Players roll the dice and try to get their counters all the way to Jerusalem without landing on the separation wall (go back to the start), a checkpoint (miss three turns), or a military prison (lose the game). Personally I think that this game has potential, and with a little work we could market it overseas as an edgy new version of Monopoly. “Chance card: you are arrested by the army as you try to sneak to your illegal job in Jerusalem. Go straight to Ofer prison. Do not pass Machsom 300, do not collect 200 shekels.” Sometimes a generous dose of satirical humour is the only way to cope with the fearful and bitter uncertainties of life here.

Reem’s method is also good – her determination to give her daughters the knowledge that their integrity and the dignity of their friends are not worth sacrificing for the scraps and tatters of freedom issued by the occupying army. I think the girls are growing to appreciate that, even if they’re not quite there yet. Maryam was awestruck by the sea when she saw it for the first time, and she would do anything not to lose the hope of going there again. Principle and conviction may support Reem and the Israeli woman who heard her story on the other side of the bars, but they must be a cold comfort to most eleven-year-old girls. They never signed up for this. They didn’t ask to be heroines or freedom fighters. Maybe one day Maryam will look back on what her mother did that day and feel proud. But for now, she and her friends just want to play.

- התחבר בכדי להגיב